Mrs. Valentina, are you a citizen of Mexico?

– Sí.

On June 23, did you enter the US near Sasabee?

– Sí.

Did you come through a designated port of entry?

– No.

How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

– Culpable.

„Guilty.“ It takes four minutes for Mrs. Valentina to become a convicted felon on this June 25th afternoon in the District Court of Tucson, Arizona. Four minutes that will change her life forever. Since 2005, entering the US illegally is judged as a felony offense which comes with a prison sentence, just as if she had murdered her husband, kidnapped a child or set fire to a building. The judge makes this very clear: “This conviction will always be on your record and it will always be used against you.” Even if she could legally return to the US, she would never be eligible for welfare, visa or a license to open a business. Employers and landlords could see the conviction on her record and discriminate against her. And in theory, her husband can now seek divorce immediately without giving a reason.

A small woman in her forties, Mrs. Valentina has to stand on tiptoes to speak into the microphone. Bending it down is no option: Her hands are cuffed and tied behind her back with a metal chain.

Nobody seems to notice. She is but one in a row of 37 and the court house – huge and cold, the complete opposite of Tucson’s dry heat and sandstone cottages – seems to engulf them all. Martínez, Gonzalez, Perez, with dusty T-shirts and pending shoulders, will be quickly forgotten as the court fills with new migrants week after week. In 2005, the Bush administration found a dauntingly efficient way to enforce immigration laws along the US-Mexican border. So efficient that the Obama administration even expanded it. What must have seemed overwhelming and chaotic to the authorities before – all those different life stories and reasons for migrating – has become a neat assembly-line process: Operation Streamline.

„Sí. Sí. No. Culpable“, is all the US needs to hear in order to convict and deport Miss Valentina. No questions as to whether she has children in the US, how long she has lived in the country already or whether she has a place to go back to in Mexico. She steps back from the microphone and the judge continues his litany, with the voice of an unnerved kindergartener: „Mister Ambrosius, are you a citizen of Mexico?“…

When Mrs. Valentina is led out of the room in a line with the others, she passes at arm’s length by my seat in the audience. Our eyes meet. I feel like crying, but try to smile. Her eyes widen – astonished, inquiring – and she quickly smiles back, before being pushed out of the door.

How had she gotten into this?

And how did I get there?

In the summer of 2015, I traveled to the United States with a McCloy Fellowship in Journalism of the American Council on Germany. This grant has been a great opportunity for me, as it gave me the chance to research a topic in-depth and on the ground that I have been following from the distance for years: the situation of undocumented migrants.

Continue reading in the PDF above or here >>

How the US restricted immigration and created the undocumented migrant over time

CC: TimelineJS template by Knightlab

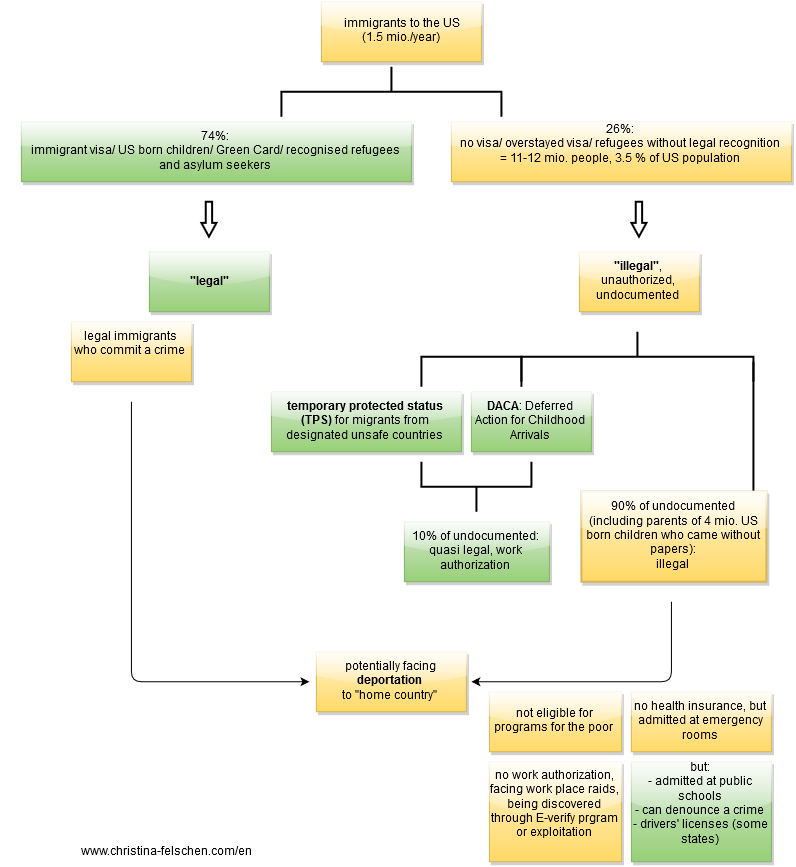

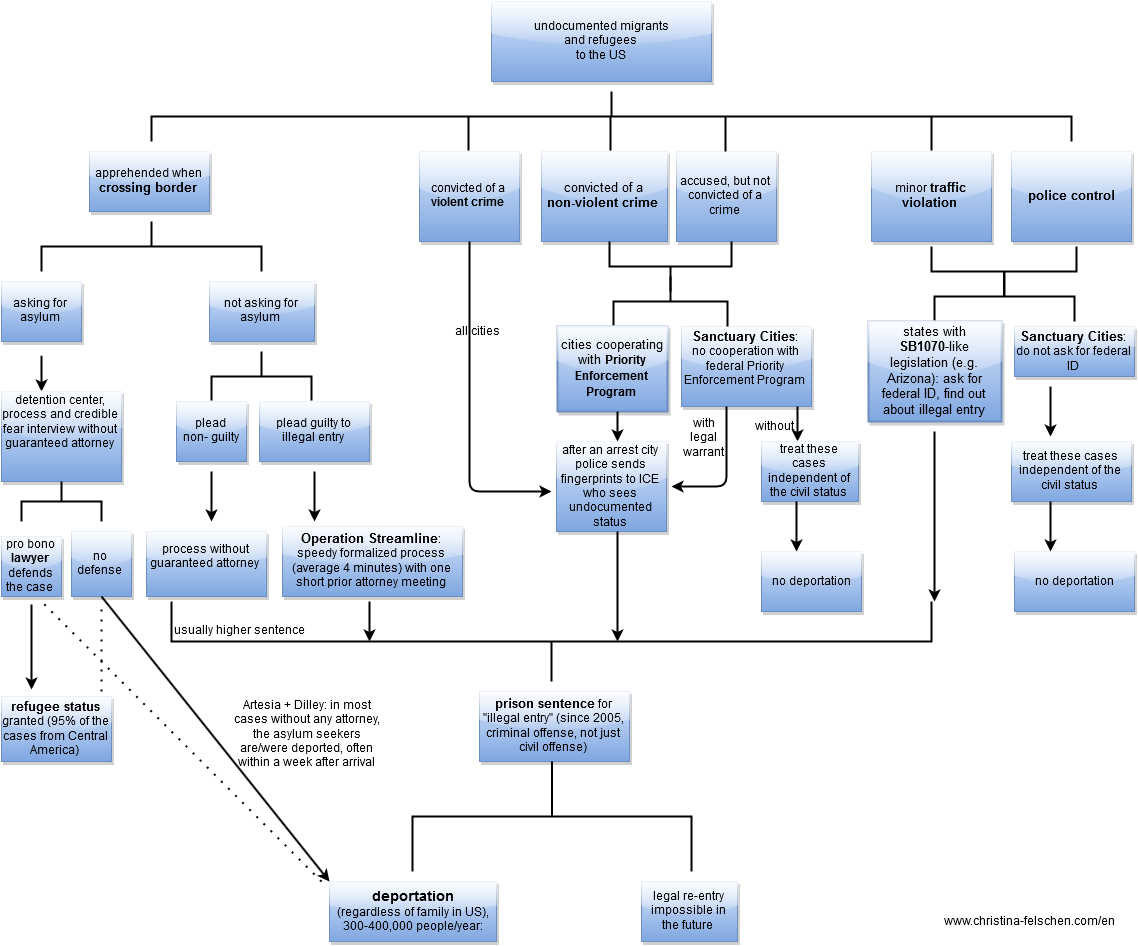

As the issue is fairy complex and rapidly changing, I became a little geeky towards the end of my research on the ground and created two diagrams that show, among others,

…why so many young people can come out as undocumented in recent years:

…why lawyers rush to detention centers in their free time to defend asylum seekers from Central America pro bono,

and what ICE and Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi are arguing about after the Pier 14 tragedy in San Francisco: