April 2015, I press my nose against the airplane window. Several miles below us, a stark white cone appears within lush green hills. It still looks enormous, intimidating even from the sky. “Shasta”, I whisper in awe – and “Shasta” echoes back from the row in front. I notice a young man that has reacted just like me, his nose against the window. I immediately know that he has climbed this mountain or at least tried to. Everyone else watches television, not realizing that a better film is passing below us.

April 2015, I press my nose against the airplane window. Several miles below us, a stark white cone appears within lush green hills. It still looks enormous, intimidating even from the sky. “Shasta”, I whisper in awe – and “Shasta” echoes back from the row in front. I notice a young man that has reacted just like me, his nose against the window. I immediately know that he has climbed this mountain or at least tried to. Everyone else watches television, not realizing that a better film is passing below us.

Three days before that flight I stood on top of Mount Shasta and although I have climbed other mountains, this one felt special.

Driving northwards from the Bay Area, you cannot miss it. The 14,179 feet giant shows up on the horizon a hundred miles before you actually reach it, a landmark on the brink of the flat Central Valley. It is the only one of the twelve Californian fourteeners that is not hidden by other high mountains somewhere in the Sierra. Thus any Pacific storm can hit it at full blow and make an ascent impossible. If you think about climbing it, the weather is the most important factor – watch it for a week and be prepared to cancel your trip even at the last minute. My partner got into a storm on Shasta once which forced his party onto their knees and caught them in a whiteout. After making only 1,000 vertical feet in five hours, they had to turn around.

A famous – and infamous – mountain

Shasta attracts dozens of climbers every day, as some of its routes are “easy” by winter climbing standards. It still requires solid planning and experience – any climber should be able to assess and avoid avalanche dangers, rescue people out of an avalanche, know how to practise first aid, have winter camping experience, hike on steep ice with crampons and have practiced stopping oneself with an ice axe. Mount Shasta is famous, but also infamous for several severe accidents every year.

Shasta attracts dozens of climbers every day, as some of its routes are “easy” by winter climbing standards. It still requires solid planning and experience – any climber should be able to assess and avoid avalanche dangers, rescue people out of an avalanche, know how to practise first aid, have winter camping experience, hike on steep ice with crampons and have practiced stopping oneself with an ice axe. Mount Shasta is famous, but also infamous for several severe accidents every year.

One of the most common risks is to slip or trip on a steep icy stretch – often because the crampons get caught on the pants. When you don’t manage to self-arrest within the first seconds of your fall you might slide down some dozen or even some hundred meters.

A less common risk is being a devotee of a New Age sect and trying to climb the mountain barefoot, but that has reportedly happened. More than 100 New Age sects and religious groups regard the volcano as a sacred source of mystical power, a UFO landing spot or believe that extraterrestrials have built a city within.

Despite its name, Avalanche Gulch is one of the safer routes. Yes, avalanches and rock fall from the Red Banks ahead are possible, but as the gulch is dotted with other climbers nearly every winter morning, there will usually be people to help if anything happens.

We spent three days on the mountain, twice camping on a beautiful plateau in Avalanche Gulch – with the luxury of walls, a lounge and a kitchen dug into the snow. We decided not to stay in the crowded base camp at Lake Helen. You can indeed climb from the trail head (Bunny Flat, 6,950 ft) to the top and return in one day, but you will miss your chance to see beautiful sunsets on the mountain, you won’t have time to acclimatize for the altitude and you will have to start your way up around 3am. We used the first and the third day for some skiing on the mountain slopes and tackled the top on the second day, leaving at 6am.

I left my alpine touring skis at Lake Helen, where my partner tied his skis to his backpack. Climbing the steep icy slope to the Red Banks is exhausting and feels very exposed. During the first – dark – hour we were amused to see most other climbers wearing face masks. But when the sun appeared, its rays endlessly reflecting on the white ground, we started to envy them. Although constantly applying sun screen, we already felt how the sun burned our chins, lips and ears.

UFOs, dragon spikes and the smell of sulphur

A lenticular cloud hovered above us – this must be where the devotees get their ideas about UFO landings from, I thought, already a little dizzy, and zigzagged upwards.

When we arrived at the Red Banks (12,820 feet), I felt relief. The worst exposure was over. Next to us, rocks protruded from the snow like spikes on a dragon’s back, and a strong wind alleviated the heat. The way continues shallowly to the left along a ridge, where you can take in the view over the surrounding mountains.

When we arrived at the Red Banks (12,820 feet), I felt relief. The worst exposure was over. Next to us, rocks protruded from the snow like spikes on a dragon’s back, and a strong wind alleviated the heat. The way continues shallowly to the left along a ridge, where you can take in the view over the surrounding mountains.

By the time we reached Misery Hill the sun had already melted the ice. But while walking got easier, the altitude made breathing increasingly difficult. We saw the first climbers suffer from altitude sickness and return. The smell of sulphur engulfed us as we continued – a reminder that Shasta is an active volcano, although its last eruption dates back more than 200 years.

We left our backpacks and my partner’s skis on the plateau before the short, but very steep ascent to the peak. But there was a final unexpected hurdle: A ranger waited for us on top. He had seriously spent the night there to check everybody’s registrations. Which were in our backpacks below. Luckily he gave in when we could describe their look.

And there we were, on the roof of the Cascade Range – Lassen Peak a white spot in the distance, the Bay Area somewhere on the horizon and any thought of deadlines far, far away.

A 6,000-feet long slide

Glissading down the entire 6,000 feet to our camp was hilarious! I immediately felt like a child again, as I tried to gain speed on the same slope that was rather terrifying on the way up. My partner skied down the whole stretch. You should be comfortable with black diamond routes – icy, steep and forcing you into occasional slaloms between the Red Banks – while wearing a destabilizing backpack. As a beginner that was no option for me.

When we came down a day later, the adrenaline was gone and I felt the effects of both altitude and sunburn. Although we hadn’t eaten nearly enough on the mountain, the thought of food made me sick for days. The sun had left a hard incrustation on my chin and lips. But all this was gone within a week, while the joy of having been up there lasts until today.

In the airplane above California, I thought of the sunsets at our camp site. Camping on the slope of a huge mountain can feel calm and protected, if the weather is good. Whatever you do out there feels existential and meaningful; you will not lose yourself, procrastinate or take stupid decisions – that would be just too dangerous. There is a way up and a way down, the rules are simple. But in between there is space for discovery: What looks like just a white slope bare of vegetation from the plane is a stunningly complex landscape, bent into hills and sudden cliffs, alternating between ice and fluffy snow. And it has its own landmarks: the debris from a small avalanche that came down from a cornice, the flat surface of an invisible lake and a tiny tent on Casaval Ridge.

A playground in winter wonderland – Lassen Volcanic National Park

If you are looking for something less intimidating and more playful to start with, Lassen Volcanic National Park southeast of Mount Shasta is a fantastic destination.

While most people come to Mount Shasta to try climbing the mountain, Lassen has a wide fascinating backcountry full of mossy conifer woods, frozen lakes, meter-high snow piles, igloos left behind by former visitors and steaming sulphur works. A playground for easy skiing, snowshoeing, hiking – and, yes, climbing Lassen Peak if you want to.

A (free) wilderness permit allows you to spend several days camping in the backcountry. Lassen Peak (10,463 feet) is just 2,000 feet higher than the trail head, so the climb is much shorter and less exhausting than Mount Shasta. It still is a good preparation for Shasta as you will need the same skills and there are certain similarities.

Just like its bigger brother, Lassen Peak is exposed to heavy storms – we faced gusts of around 45 mph during our climb. We took our skis half way up and went the rest with ice axes. Crampons would have been helpful as there were some steep icy stretches as well, but we didn’t take them.

The view was beautiful; from the top we could even see Mount Shasta. But it is hard to take in the view when a storm catapults showers of ice crystals into your face and bends your body away from it just as it does with those crooked trees that hold out on some arêtes – but certainly not on this one. No single loose snow flake was left on our path. Instead the constant wind has formed the ice into horizontal stalagmites and painted mandalas of ice onto the rocks.

In the moment of climbing I find many mountains exhausting, but quickly forget about it later. This includes Lassen Peak on that stormy day. But the most important criterion for me is whether I felt that I might fall or that I might not make it to the top. Both thoughts hardly ever cross my mind – certainly not on Lassen Peak – but on the long ascent to Mount Shasta, they did.

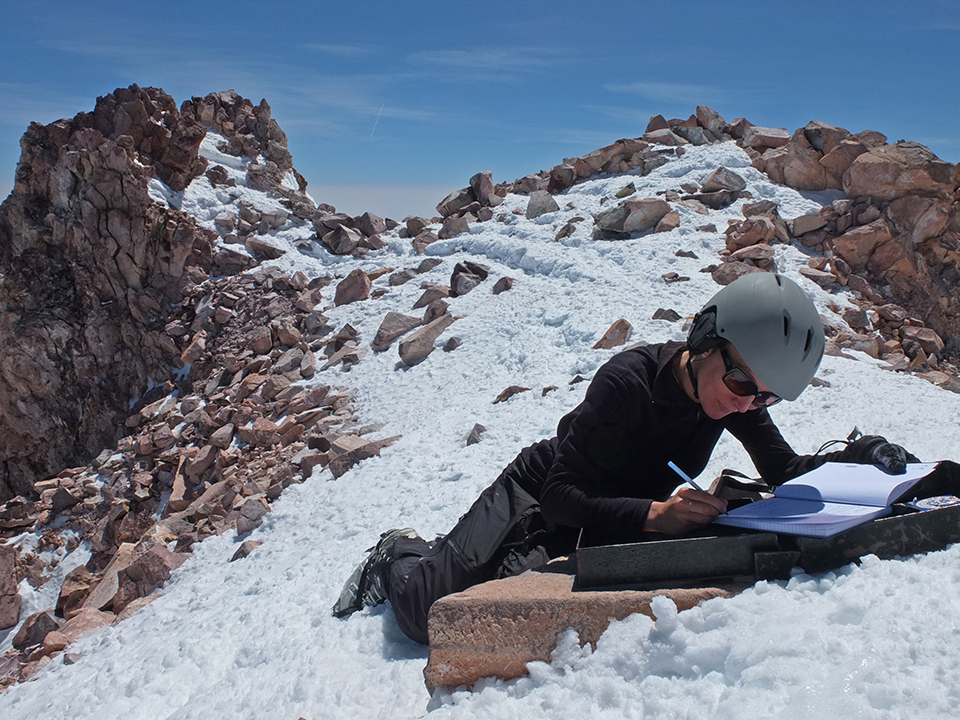

(Featured image on top: Cozy night under a volcano (in Lassen’s backcountry). I am mixing Shasta and Lassen pictures as the difficult ascent to Mount Shasta did not allow me to take many photos.)

You can find more ideas for trips that favor human over horsepower in the California Outdoor Calendar. If you have additional ideas or questions, please leave a comment below.

When to go: March to May is the ideal time for visiting Lassen or Shasta. While the skiing season nears its end around Lake Tahoe, there will still be sufficient snow in the Cascade Range. Horse Camp at Shasta’s bottom (7,900 feet) opens around April/May; it offers access to water and a toilet. In summer Mount Shasta becomes a huge pile of rubble which is not fun to climb.

Before you go: Check the weather and avalanche forecast (the latter only exists for Mt. Shasta, but can be applied to nearby Lassen National Park), road conditions and read the park rules. Mount Shasta and Lassen National Park have no mobile network, so leave a detailed tour description with friends (Shasta)/ with the rangers (Lassen).

What to read: The Mt. Shasta book. A guide to hiking, climbing, skiing, and exploring the mountain and the surrounding area, Andy Selters and Michael Zanger, Ilderness Press, 2006. + 50 Classic Backcountry Ski and Snowboard Summits in California, Paul Richins, Jr., The Mountaineers Books, 1999. (chapters on both Shasta and Lassen)

What to take: skis (or snow shoes), winter tent, avalanche rescue kit (beacon, shovel, probe), headlamp with spare batteries, compass/GPS device/spot tracker, sunscreen, sunglasses, possibly base cap that you can wear on your helmet and bright cloth to protect your mouth from the intense sun (especially for Shasta) , warm clothes for nights, hand sanitizer, first aid kit, enough water for a day (the rest can be melted at night), dry food, a vehicle pass to get into Lassen National Park ($20 or just get an Annual Pass for all National Parks at $80), permits (at the trail heads; for free at Lassen, $20 at Shasta) and “shit kits” provided at the trail head at Shasta (or better ones from REI) as you have to pack out human waste. Print yourself a Caltopo map of the area.

What to take: skis (or snow shoes), winter tent, avalanche rescue kit (beacon, shovel, probe), headlamp with spare batteries, compass/GPS device/spot tracker, sunscreen, sunglasses, possibly base cap that you can wear on your helmet and bright cloth to protect your mouth from the intense sun (especially for Shasta) , warm clothes for nights, hand sanitizer, first aid kit, enough water for a day (the rest can be melted at night), dry food, a vehicle pass to get into Lassen National Park ($20 or just get an Annual Pass for all National Parks at $80), permits (at the trail heads; for free at Lassen, $20 at Shasta) and “shit kits” provided at the trail head at Shasta (or better ones from REI) as you have to pack out human waste. Print yourself a Caltopo map of the area.

Alternative approaches to Mount Shasta: Casaval Ridge on the left of Avalanche Gulch offers an alternative way to the peak. Be prepared for stretches with 50-degree inclination (as opposed to 35-40 degrees in the Gulch), where you have to front point your crampons into the snow. Many people take ropes to secure each other on the most difficult stretches, but it is possible to go without. People usually don’t take their skis up there, as you have to path your way through rubble. Most people glissade down the Avalanche Gulch as the Ridge is more difficult on the way down, so you might want to go in one day or take your tent to the top. The summit post website describes this and other routes – the circumnavigation, Shastina etc. – with more detail.

Alternative approaches to Mount Shasta: Casaval Ridge on the left of Avalanche Gulch offers an alternative way to the peak. Be prepared for stretches with 50-degree inclination (as opposed to 35-40 degrees in the Gulch), where you have to front point your crampons into the snow. Many people take ropes to secure each other on the most difficult stretches, but it is possible to go without. People usually don’t take their skis up there, as you have to path your way through rubble. Most people glissade down the Avalanche Gulch as the Ridge is more difficult on the way down, so you might want to go in one day or take your tent to the top. The summit post website describes this and other routes – the circumnavigation, Shastina etc. – with more detail.

Have you climbed Mount Shasta or are you planning to go? Please comment on my Instagram post!

Sieh dir diesen Beitrag auf Instagram an

Any questions? Here on twitter: @chessocampo